Thanks to my technical incompetence, I am now reconstructing (on another computer) what I had spent many hours on yesterday, i.e., the graphic “Powerpoint” supplement to the talk on “Heroism and the Struggle for Liberty” that I’ll be giving at a conference this week on Grand Cayman. After ten or more hours of looking for, finding, and copying images to accompany short quotations, it crashed my computer. So….all over again. I should have done what smart people my age do, and ask a 20-year-old intern.

In any case, here’s one cool image I found for Enkidu, the natural man who challenges Gilgamesh the mighty king in The Epic of Gilgamesh:

Enkidu

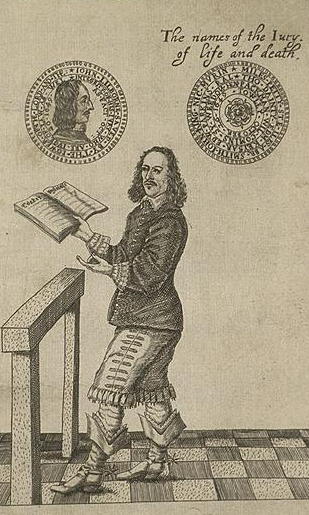

And here’s the great English Leveller hero, John Lilburne:

John Lilburne

I may be out of computer range for a while and am not sure whether my Blackberry will work. Ack!

The other smart thing people our age tend to forget is the frequent use of the “save” key. You only lose what you haven’t saved…from one who’s learned the hard way, over and over again.

RL

How cruel, Ross, how cruel. And, in any case, I *did* save, but somehow the file became corrupted and wouldn’t open up again, leading to much gnashing of teeth, pulling of hair, and other strange behavior that greatly upset my cats.

Save and backup to recoverable media, i.e. ZIP drive, CD-ROM, floppy, or, as I do, iPod hard disk. Often files that we need to most are seemingly the *first* silly things to just up and disappear.

Yes, using some type of other media as backup is a very good idea (I use a ZIP drive myself for small files and burn CD’s for large ones).

Another good idea with the temperamental Powerpoint, whenever preparing multimedia presentations, is to first prepare (and save) a text-only version and only then add the multimedia files (while also keeping separate backups of these files).

It’s a little bit more work but I think the discipline pays off in the end (I recently worked on a project that involved several hundred slides and close to one hundred media files and this method made it possible to survive a couple of crashes with only minor damage).

Aside from backing up your work, it is also a good idea to split up huge documents into smaller files. Not only does this reduce the chance of corruption, it also means you lose much less if corruption does occur.

I love the Epic of Gilgamesh, though I’m not sure what Enkidu has to do with the struggle for liberty, unless maybe as an allegory for rebellion against tyranny, though not a very good one since he ends up befriending Gilgamesh. I prefer to think the lesson of the struggle between the two is that men require physical exertion and contest, otherwise they become despotic and cruel. In other words, we should make George Bush wrestle the head of the next country he wants to invade, and see if he still wants to make war after its all said and done.

On a corollary, I don’t trust any man who did cheerleading in college. That’s not even a sport, just a social activity that involves acrobatics, euughhh.

Thanks to Brian, Ross, Andre, and Henri for the pointers on backing up. (I had been saving, but somehow it ended up with a totally bolloxed system. Last year I bought a Mirra system to create systematic backups, but it couldn’t get along with my DSL modem and my WiFi router and many, many hours couldn’t sort it out.) I’ll probably get one of those one-button-push backup systems this week.

Mr. Gurr raises a good question about what the Epic of Gilgamesh has to do with the struggle for freedom. The background to my use of the Epic of Gilgamesh is that I see freedom in society not as being completely unrestrained, but as being subject to the law, rather than to arbitrary power. John Locke does a good job in the Second Treatise (Chap 6, “Of Paternal Power,” Section 57) of setting out the relationship between law and liberty:

“[T]he end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom: for in all the states of created beings capable of laws, where there is no law, there is no freedom: for liberty is, to be free from restraint and violence from others; which cannot be, where there is no law: but freedom is not, as we are told, a liberty for every man to do what he lists: (for who could be free, when every other man’s humour might domineer over him?) but a liberty to dispose, and order as he lists, his person, actions, possessions, and his whole property, within the allowance of those laws under which he is, and therein not to be subject to the arbitrary will of another, but freely follow his own.”

So the struggle to escape from the arbitrary power of a man or group of men is essential to the story of freedom. One means of escaping from such power is to oppose power to power (hence the importance of, for example, the right to keep and bear arms). Thus (in the Andrew George translation of the Standard Version of the Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic, with material in brackets supplied from the context of the poem, parallelism, etc.), we find that,

“[Though powerful, pre-eminent,] expert [and mighty,]

[Gilgamesh] lets [no] girl go free to [her bridegroom.]

The warrior’s daughter, the young man’s bride,

to their complaint the goddesses paid heed.”

That’s the character of unrestrained and arbitrary power. But the people pray to the gods, who create a champion for them:

“[Let]them summon [Aruru,] the great one,

[she it was created them,] mankind so numerous:

[let her create the equal of Gilgamesh,] one mighty in strength,

[and let] him vie [with him], so Uruk may be rested.”

The worst thing is to be subject to the arbitrary power of others. Power, however, can check power, and when Enkidu fights with Gilgamesh before the door of the wedding house, Gilgamesh ceases (as far as we can tell) his predation on the young women of Uruk.

There is, of course, a great deal more to the story, including the erotic friendship between Enkidu and Gilgamesh, their adventures, the death of Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s search for the secret of immortality, and much more. What is interesting from the perspective of the story of liberty is the the description of what it is like to be subjected to arbitrary power and the possibility that power can be checked with countervailing power. (Lest this only bring to mind the system of checks and balances in the U.S. Constitution, think also of the importance of the Gregorian Reformation of the Church, also referred to as the Investiture Crisis, and the significance for western European liberty of the independence of the church from the secular rulers and the ability of each to check the other. It was in those “jurisdictional cracks” that individual liberty was able to take root.)

First, it’s Mr. Gunn, no offense taken.

Second, I am bemused at your assertion that Gilgamesh and Enkidu had an erotic relationship. I must admit it is something I hadn’t considered before, and I suspect you may be taking some literary license, though of course neither of us are qualified to claim interpretative authority on a 5000 year old dead language. The Epic is quite explicit about both Gilgamesh’s penchance for rape and Enkidu’s seven day tryst with Shamhat, I cannot imagine why the author would wax demure if they were sexual partners. I believe the traditional interpretation is that they shared a very intimate filial love, rather than an erotic one. Maybe you could explain to me why there’s a good reason to believe otherwise.

Dear Mr. Gunn,

I apologize for the typo! I knew that your name was spelled with two “n”s and, since “n” and “r” are rather far apart on the keyboard, I’ve no idea why I mistyped your name.

Now, on to the mentioning of the erotic relationship between Enkidu and Gilgamesh. Now I could just write that “eros” does not always refer to sexual coupling, but I suspect that that is one of the ways that Enkidu and Gilgamesh were bound together.

Let’s look at the text.

Stephen Mitchell notes in his introduction to his new arrangement of the Epic, “The poem comes just short of stating that the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu is homosexual (in Tablet XII, a separate poem appended to the epic, the genital sexuality is explicit). But it’s clear that the homoerotic element in their bond is very strong. Even before he meets Enkidu in combat, Gilgamesh dreams of him in an image of great physical tenderness.” (p. 23) [I have examined several translations of Tablet XII and could not find the explicit genital sexuality, unless the “pukku” and “mekku” that Gilgamesh seeks are references to genitalia; some translators surmise that the references are to the “ball” and “mallet” with which the heroes have been playing.)

In any case, all of the translations of Tablet I of the Standard Version have language such as the following (from the translation by Stephanie Dalley in the Oxford Classics edition),

“O Enkidu, change your plan for punishing him!

Shamash loves Gilgamesh,

And Anu, Ellil, and Ea made him wise!

Before you came to the mountains,

Gilgamesh was dreaming about you in Uruk.

Gilgamesh arose and described a dream, he told it

to his mother,

‘Mother, I saw a dream in the night.

There were stars in the sky for me.

And (something) like a sky-bolt of Anu kept

falling upon me!

I tried to lift it up, but it was too heavy for me.

I tried to turn it over, but I couldn’t budge it.

The countrymen of Uruk were standing over [it].

….(TGP: Lines Skipped…)….

I loved it as a wife, doted on it,

[I carried it], laid it at your feet,

You treated it as equal to me.’

….(TGP: Lines Skipped…)….

She spoke to Gilgamesh,

[TGP: Repetition of Earlier Text]]

‘And you treated it as a wife, and doted on it:

(It means) a strong partner shall come to you,

one who can save the life of a friend,

He will be the most powerful in strength of arms

in the land.

His strength will be as great as that of a sky-bolt

of Anu

You will love him as a wife, you will dote upon

him.

[And he will always] keep you safe (?).

[That is the meaning]of your dream.'”

That sounds like a pretty close relationship; the comparison is to the relationship between a husband and a wife, who dote upon each other. Combined with the many references to close physical contact, it seems hard to avoid the conclusion that the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu probably shared much in common with the relationships between Achilles and Patroklus, Alexander and Hephaestion, J. Edgar Hoover and Clyde Tolson, and many other partners.