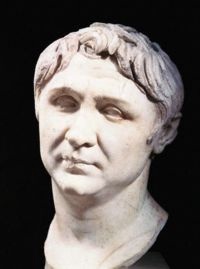

Pompey the Great

Robert Harris, the author of the excellent book Fatherland and of the new book (I’ve not read it, as I gave my brand new copy to Jose Pinera, who was about to take a long plane ride to Prague) Imperium, recently had a most interesting comparison to make between the Roman and the American Republics, in his September 30 New York Times essay on “Pirates of the Mediterranean.”

As Harris writes,

Over the preceding centuries, the Constitution of ancient Rome had developed an intricate series of checks and balances intended to prevent the concentration of power in the hands of a single individual. The consulship, elected annually, was jointly held by two men. Military commands were of limited duration and subject to regular renewal. Ordinary citizens were accustomed to a remarkable degree of liberty: the cry of “Civis Romanus sum” – “I am a Roman citizen” – was a guarantee of safety throughout the world.

All of that was swept away by the quest for an imperial power that was justified in the name of security from pirates.

Odd, I remember the Roman Republic as being quite repressive of non-citizens through out its history. Thus, the parallel with current policy for non-uniform combatants fails. It wasn’t a step made to restrict the rights of non-citizens that was the downfall of the Republic, was it? One the contrary, in the next 300 years the Roman Empire will continuously expand the rights of citizenship and become one of the most tolerant, indeed over-tolerant, society prior to the Enlightenment. Of course, that’s holding the bar very low.

Compared to the Patriot Act, we’ve witnesses much worse in our history. Lincoln and Wilson enacted measures far harsher than Bush. But unlike Bush, they fought real wars not “wars” against a tactic (“terrorism”) and when the wars ended there was a general, if not perfect, restoration of procedural rights even if property rights continue to be eroded.

Perhaps a better comparison to the pirates in Ancient times would be today’s Mafia and the RICO laws used against American citizens to fight crime. A comparison of an ideologically-driven enemy with widespread support (Islamism) to ancient pirates seems silly. Indeed, such an analogy makes Harris’ striking the cord of fear seem excessive as well. That doesn’t help us get the prospective we need. The sky is falling? Perhaps someday the person saying that will be right; and when they are the crowd will honor their prescience. I won’t be in that crowd.

I meant to mention that the Palmer Raids would be a more interesting comparison: terror bombings, ideological movements, privacy rights ignored, expansion of federal power, deportations, etc. Don’t you agree?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palmer_Raids

http://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/hist409/palmer.html

Such comparisons are always a matter of context. Compared to other states, the Roman republic had a fairly good track record in terms of providing legal order and a relative degree of freedom for their citizens. Slavery was a brutal fact of life throughout the ancient world. The Roman law, shocking as it was to the modern conscience, evolved toward a relatively liberal (and I stress relatively) form in its treatment of slaves, compared to its origins.

I don’t agree that the Palmer raides are much more helpful as a comparison. Military adventurism certainly played a major role in undermining the Roman republic and I think that the comparisons made by Harris, while necessarily imperfect, are more enlightening. Republican forms are exceptionally difficult to maintain in the face of military adventurism.

So why was the Roman Empire more “bad” or “evil” than the Roman Republic? You also have a hard time proving that the Roman Empire was more authoritarian or anti-libertarian than the Republic. Certainly the standard of living went up for more citizens, at least in the early days of the Empire.

You have to do better than “Republic = Good, Empire = Bad.” The British Empire, for exaple, was a force of liberty for several hundred years. Yes, yes, I know that “American Empire” is evil evil, just like the Galactic Empire in Star Wars. But you need to actually prove that empires are evil/bad.

That’s a worthy challenge. The subjugation of the entire population to the whim of one person — the emperor — with no checks on his powers is a defining characteristic of a lack of liberty. That the standard of living continued to go up during the late Republic and the early period of the Empire (starting with Octavian = Augustus) had something to do with the extension of the Roman law, which carried with it substantial degree of certainty and objectivity, to more people, with a corresponding increase in the productivity of labor and investment and in the extent of trade, and with it a wider extent of territory over which people were freer to travel, which further contributed to the extension of freedom to more people. Yet that very same system of law was undermined by the power of Emperors to exert their personal powers, without constraint of law. The result over time was an erosion of private rights, an decrease in the certainty and objectivity of the law, and the decline of what liberty had been enjoyed in the past.

Your response isn’t very historical.

Look up the “Constitutio Antoniniana.”

This is a quote from the Wikipedia

entry on the Constitutio Antoniniana, which is brief but accurate:

“The reasons Caracalla passed this law were mainly to increase the number of people available to tax and to serve in the legions.”

Call it “citizenship” if you like, but Emperor Caracalla’s reform is

really about taxes and forced conscription, with no compensating protection of rights whatsoever. Caracalla’s other acts show him to have been an utter tyrant, one of the worst to be seen in the ancient world. It does not excuse him that he extended a predatory “citizenship” to a people who cannot possibly have wanted it.

Even tyrants can expand rights. Was the 13th Ammendment really about taxes and forced conscription? Sorry, still not buying the “it’s an empire, so it’s evil” theory. The Roman Empire had ups and downs over its 1000 year history, but the Republic was a far worse institution.